Best Exercises for Rotator Cuff Strength and Injury Prevention

2. Internal Rotation with Resistance Band

Internal Rotation with Resistance Band: A Key Exercise

This often-overlooked movement balances the shoulder's force couples. While external rotation exercises receive more attention, internal rotation strength remains vital for functional movements like pushing, pulling, and rotational sports. The subscapularis - the rotator cuff's strongest muscle - responds particularly well to band training. Controlled resistance through the full range maintains joint congruency while building strength.

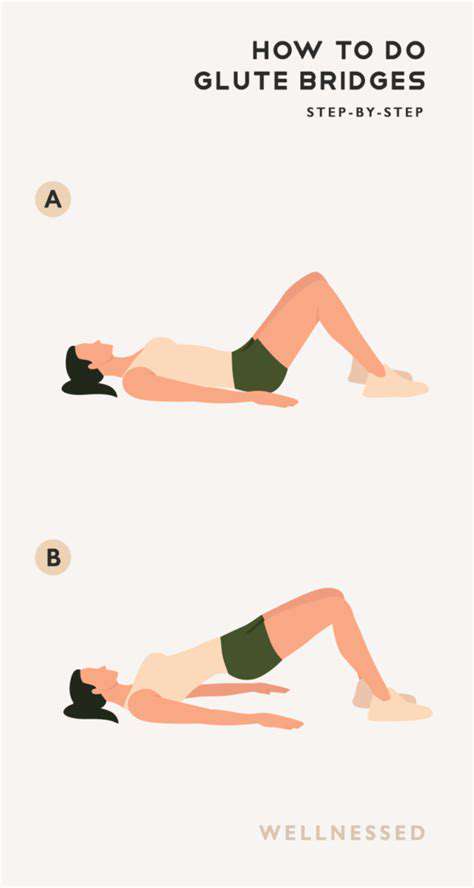

Proper Form for Internal Rotation

Anchor the band at waist height and stand facing the attachment point. Keep the elbow flexed to 90 degrees with the upper arm secured against the body. Rotate inward until the hand reaches the midline, maintaining scapular stability throughout. The movement should originate from the shoulder joint, not the elbow or wrist. Avoid the common mistake of allowing the shoulder to hike upward during the motion.

Targeting Specific Muscles

Electromyography studies show peak subscapularis activation occurs during resisted internal rotation. The teres major and pectoralis minor act as important synergists during this movement. Balanced development of these muscles prevents the common internal rotation dominance seen in many athletes. This exercise proves particularly beneficial for baseball pitchers, swimmers, and tennis players who require explosive internal rotation power.

Resistance Band Selection and Adjustments

Unlike external rotation, internal rotation typically allows for greater resistance due to the involved muscles' natural strength. However, the same progression principles apply - begin with manageable resistance and focus on quality movement. Adjusting the anchor point height changes the resistance curve, with lower anchors emphasizing the end range. Many rehabilitation protocols recommend slightly higher reps (15-20) for internal rotation compared to external rotation exercises.

Warm-up and Cool-down Procedures

Dynamic warm-ups might include arm swings and cross-body stretches. Post-exercise static stretching helps maintain internal rotation range, which often becomes limited in overhead athletes. Foam rolling the pectoral and latissimus muscles can enhance exercise effectiveness by reducing soft tissue restrictions. Many therapists recommend ending the session with scapular retraction exercises to counterbalance the internal rotation focus.

Progression and Exercise Variations

Advanced variations include performing the exercise at varying degrees of shoulder abduction or incorporating isometric holds. Some protocols combine internal rotation with diagonal patterns to simulate sport-specific motions. Eccentric overload training (slowing the return phase) benefits those recovering from certain types of rotator cuff repairs. Always prioritize pain-free range of motion over resistance level when progressing the exercise.

Safety Precautions and Common Mistakes

Watch for compensatory trunk rotation or loss of elbow position. Those with anterior shoulder instability should monitor for subluxation sensations. Pain at the front of the shoulder during the exercise may indicate biceps tendon irritation. Many clinicians recommend avoiding maximal internal rotation stretches immediately after heavy resistance training of these muscles.

Read more about Best Exercises for Rotator Cuff Strength and Injury Prevention

Hot Recommendations

-

*Guide to Managing Gout Through Diet

-

*Best Habits for Financial Well being

-

*How to Build a Routine for Better Mental Health

-

*How to Eat Healthy on a Budget [Tips & Meal Ideas]

-

*Guide to Practicing Self Acceptance

-

*How to Incorporate More Movement Into Your Day

-

*Guide to Managing Chronic Pain Naturally

-

*Guide to Building a Reading Habit for Well being

-

*Top 5 Weight Loss Supplements That Actually Work

-

*Best Exercises for Postpartum Recovery [Beyond Abdominal Work]